Does oclacitinib predispose dogs to develop cancer?

Dear Colleagues,

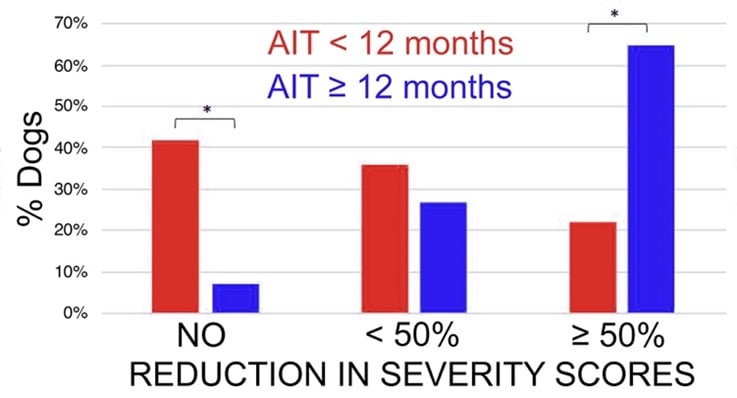

For this month’s newsletter, let’s move to another chapter in the management of canine atopic dermatitis (AD). As you all know, the treatment of this disease is multifaceted. In the first phase of treatment of a dog with active clinical signs—a stage that we call "reactive therapy"—the goal is to induce the promptest remission of symptoms, or, in other words, "to induce disease control." In contrast, allergen immunotherapy is an important pillar of the second phase of AD treatment (“proactive therapy"), which is to prevent disease flares (i.e., "to keep disease control”) in a dog whose signs are successfully treated with anti-allergic drugs.

In the 1980s and 1990s, oral or injectable glucocorticoids were the only drugs shown to be consistently effective to control signs in most—if not all—dogs with AD. With ciclosporin's introduction in the early 2000s (Atopica, Novartis Animal Health, now Elanco), a new era of long-term control of signs of AD with immunosuppressants arose.

In 2014, Zoetis launched the first-in-class Janus kinase nonselective (yet JAK1-predominant) inhibitor oclacitinib (Apoquel). This was a revolution in the treatment of canine AD due to its rapid effect to reduce atopic itch, with a noticeable benefit within hours of the first pill. Apoquel soon became a blockbuster drug in all countries where it was launched.

Both ciclosporin and oclacitinib are T cell immunosuppressants, which is why they are so effective in treating signs of canine AD, albeit with different speeds of action. As these drugs both decrease T cell function, they might, induce clinical immunosuppression in dogs whose immune system is sub-functional, for example, in some juveniles, in some senior dogs, in patients with a subclinical (genetic?) immunodeficiency, or if the drug is used off-label at higher dosages or frequencies of administration. There are, indeed, rare occurrences of unusual infections or infestations with either one of these two drugs. Luckily, a short treatment vacation—with or without specific treatment of the infection/infestations—usually results in the prompt disappearance of signs once the immune system returns to its functional status.

After the launch of both Atopica and Apoquel, worries were expressed in the dermatology community that each of these drugs might lead to cancer development in the long term because of their immunosuppressive effect on T cells.

It took a more than a decade to be reassured that we did not see any cancers following the long-term treatment of atopic dogs with ciclosporin. For oclacitinib, we are lucky to have a publication to alleviate these unfounded fears.

In a recent paper, Brittany Lancellotti and her colleagues from Southern California reported the results of a well-designed, retrospective, case-controlled study to address the question of whether oclacitinib could be associated with cancer development in the medium term (Lancellotti et al., J Amer Vet Med Assoc 2020).

The investigators reviewed the medical records from 339 dogs with allergic dermatitis treated with oclacitinib for at least 6 months (range: 6-58 months) and followed-up for more than 2 years; this was the “case” or the (oclacitinib)-“exposed” group.

A second group was formed of 321 allergic dogs that had not been treated with oclacitinib but that had received standard-of-care drugs (e.g., glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, antihistamines) and/or allergen-immunotherapy with a follow-up greater than 2 years.

Importantly, the dogs from this “control” (i.e., [oclacitinib]-“non-exposed”) group were age- and breed-matched to those of the first group!

The main outcome measure was comparing the cumulative prevalence of masses (including malignancies and benign skin masses) between the two groups.

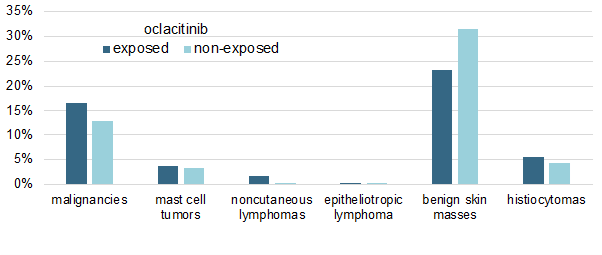

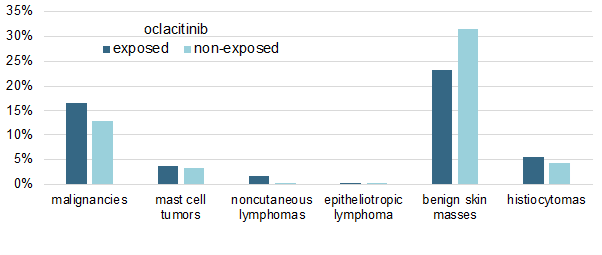

I have summarized the study's main results in a single figure in which I am showing the cumulative percentages of malignancies in both oclacitinib-treated and non-treated allergic dogs.

As shown above, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of any tumor type between the two groups, except for the oddity of an apparent, yet significant (P < 0.019), lower prevalence of benign skin masses in oclacitinib-treated dogs.

Finally, another important finding is that the dosage of oclacitinib received by the dogs did not influence their probability of malignancy development.

The results of this study are important. In my opinion, they should alleviate the fears that the treatment of AD with immunosuppressants will lead to cancer, at least in the medium term. To add to this, I am not aware of any report that the treatment of atopic dogs with either ciclosporin or oclacitinib is associated with the development of malignancies in the even-longer term (i.e., years).

Finally, veterinarians should be aware that AD, in itself, predisposes dogs to develop cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) (Santoro, Vet Dermatol 2007). So, if you see an atopic dog with lesions cutaneous lymphoma, don't immediately blame the ciclosporin or the oclacitinib!

Till next month!

Respectfully submitted,

Thierry Olivry, DrVet, PhD, DipECVD, DipACVD

Research Professor of Immunodermatology

NC State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

Scientific Advisor and Dermatology & Allergy Consultant

Nextmune, Stockholm, Sweden

UK

UK

Global English

Global English

-Dec-21-2023-09-46-12-9148-AM.jpeg)